Magic Math, Magic Mushrooms, and Magic Monkeys

If asked to recall famous physicists, most people will name Newton and Einstein. Some may mention Feynman or Curie or Hawking. Relatively few will mention Maxwell, even though the equations he came up with are perhaps the most remarkable.

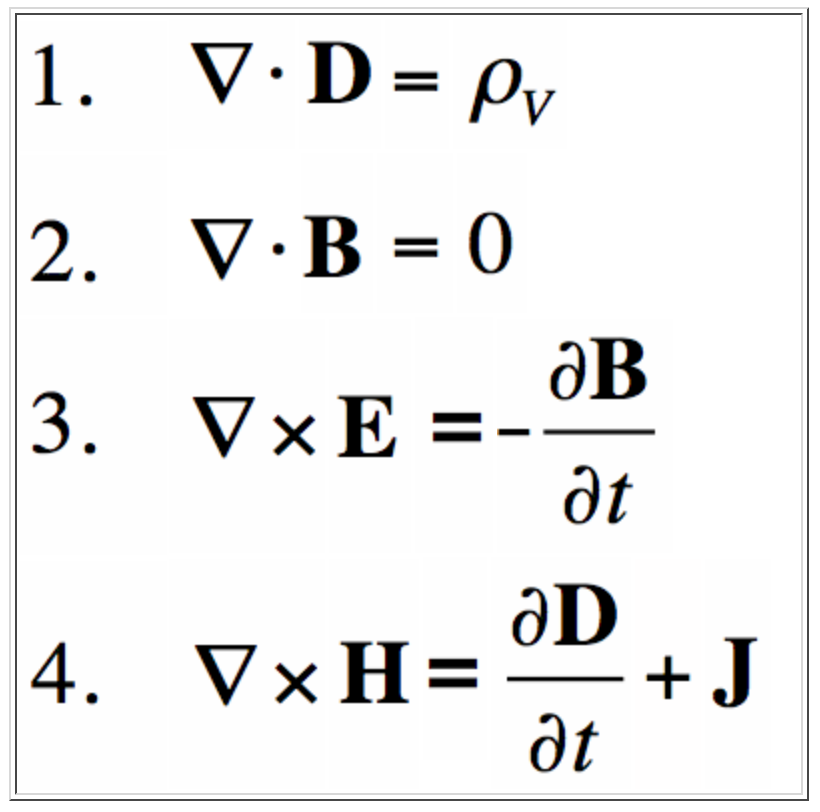

For background, Maxwell provided us four relatively simple differential equations (listed below) that describe the behavior of light. What’s remarkable about these equations is that they are correct. It’s a great tragedy of history that Newton is so well known for his laws of motion (that are actually wrong), while Maxwell is not known for his laws of electromagnetism, which have been subject to endless scrutiny and have proven extremely accurate.

We have very good simulations of these equations. Maxwell’s equations can be used to simulate radio wave propagation, semiconductor behavior, magnetism, and the stars. They are widely applicable and, while adjustments have been made to them in order to better capture our modern understanding of the universe’s geometry, the fundamental statement of the equations has been found to be correct.

So it’s very unfortunate then that his equations are also wrong.

They’re wrong not because they aren’t right, but because they don’t characterize that which they describe.

Here’s a thought experiment, when we simulate a radio wave or a semiconductor, is that the same thing as the real thing? Even if we get our simuation perfect, so that it is at 100% fidelity, we can still distinguish between the simulation which is only portaying what reality could be, and reality itself. Put another way, if I simulate a magnet on a computer, and hold a compass near by, will the compass move?

So in the sense that Maxwell’s equations only describe the electromagnetic force, rather than tell us what the force is, the equations are incorrect. A description of something is not a statement on its nature.

In fact, we know very little about the electromagnetic force in terms of what it actually is. Most physicists today have adopted the “shut-up-and-calculate” approach, due to how seemingly intractable it is to use empirical measurements to get at the underlying reality of the universe. Again, I don’t want to diminish these efforts. They are truly remarkable, and extremely useful for the problems humans have to solve. But, for now, inquiries into the nature of reality may have to break from them.

Magic math

There’s a view in artificial intelligence that I call the “Magic Math” hypothesis. Proponents of this hypothesis, of which there are many, purport that by creating a mathematical description of intelligence and then optimizing it to behave in a way resembling humans necessarily gives rise to the same sort of internal experience or consciousness that characterizes humans. They point out that we ourselves only have evidence for our own internal experience, and rely on observation alone to note it in others. They are not totally wrong. Again, like Maxwell, we are forced to deal with only a description of other’s experiences, rather than their fundamental nature. They point out then, that we have no reason to believe that the AI systems being created today don’t similarly have an inner experience of some sort, because we can observe the same descriptive attributes on them that we observe in others.

In other words, since they’ve gotten the math correct, and the math accurately describes reality and is being calculated so that it seems like it’s reality, then that’s enough.

To me this argument is not compelling. As we’ve already established, even a 100% faithful simulation of something is not the same thing as the thing itself.

Thus, their reasoning for their claim ought to be rejected and the status of their claim (that AI does have a kind of inner experience) is back at something that has no real proof either way.

Magic mushrooms

A last resort treatment for epilepsy is called a Corpus callosotomy. In this procedure the corpus callosum, the bundle of nerves connecting the left and right portions of the brain are severed. One of the results of this is that the two hemispheres (left and right) have trouble communicating with one another.

A result of this in some patients is that one side of their body (usually the left) takes on a mind of its own. This is called ‘callosal syndrome’. In one case, a patient who had undergone this procedure would have two sides of his body in conflict 1. Wikipedia recounts the story of a man whose one side was violently beating his wife while the other side rushed to save her. Were both ‘sides’ aware?

In the same way that a callostomy reduces the experience of consciousness, psychedelic drugs have been claimed to expand it. For example, many who have taken magic mushrooms claim that it has expanded their sensation of consciousness and given them access to feelings beyond their body. Again, this furthers the materialist (or partial materialist) view that consciousness ‘runs’ on material reality. If drugs in our mind can turn consciousness on, or amplify the way it feels, then there must be something physical going on that we can describe somehow.

One of the omnipresent concepts in quantum physics is that of a field. Many things are fields. You’ve probably heard about the electromagnetic one. There are others – gravity, the ‘color’/strong force, etc. Particles also have fields. So there’s an electron field, a proton field, etc.

In general, a field is nothing more than a function \(F: \vec{X} \rightarrow D\), where \(\vec{X}\) is some location in space-time and \(D\) is some measurement. For example, the electric field \(q: \vec{X}; \rightarrow Q\) maps each location in the universe to the charge present at that location. There’s also the electromagnetic force field, \(V: \vec{X} \rightarrow \vec{V}\) which maps to each point in space the electromagnetic field potential present there (relative to some other point – usually expressed as voltage).

In the same way there’s a field for all of these, there’s also a field for unicorns, elephants, and rainbows 2. Again, we have to be careful to avoidd the mistake of confusing the description of a thing with the thing itself. A field is just a mapping. If we can make the statement “There’s an elephant there” (even if only conceptually), we can model it as a field. It’s just as real as the other fields. It’s just a description of reality.

Of course, fields can depend on one another. The magnetic field is intrinsically linked to the electric field. That is to say, it’s a function of the electric field. In other words, if you know the electric field, you can determine the magnetic field.

\[\vec{B} = f(\vec{E})\]

This relation and its inverse are used to transmit electricity and radio stations. Moreover, the fields are related to matter (the arrangement of electrons mostly).

\[\vec{E} = f(e^{-})\]

In fact, we cannot manipulate the electrical field directly. We do it by moving matter. One only need to visit a power generating station to see how we use matter to manipulate these fields on a grand scale. Being unable to interact with a field directly does not make it less real.

So going back to ‘reality’, whatever it is, consciousness is just as ‘real’ as anything else. We have tools to manipulate it by manipulating the other fields that we can directly observe and move.

In this interpretation, consciousness is now at least function of material reality (all those particle fields, force fields, etc). Perhaps it’s also a function of some hitherto unknown field. Either way, it’s all just as ‘real.’

Magic monkeys

Futurist and science-fiction writer Arther C Clarke said that any sufficiently advanced technology is indistinguishable from magic. Indeed the language models we have today would seem like witchcraft to any previous civilization, yet they’re just a basic application of the idea of matrices, which are first known to have arisen in the Chinese Text “九章算术” (The Nine Chapters of Mathematical Art).

Knowing that consciousness is partly material still does not really help us because we haven’t shown that it’s totally so. We know that we can take non-zero values of the consciousness field and affect them, increasing or decreasing them (apparently), but the only way we know to make it go from zero to anything else is by making a new human (another materially-involed process). If there’s more to it, a non-materialist could be justified by saying we have no material means to make it take these large leaps.

But since we don’t really understand how any of it works, I think it’s safe to say that, by our current understanding, humans (and some mushrooms?) are magic, but their mathematical descriptions are not.